Must Batman be crazy? Superman uses his natural alien powers to protect Metropolis and finds time to marry Lois Lane in the process. Spider-Man swings across New York cracking wise as he goes. But Bruce Wayne dresses like a bat every single night without time off and makes it his utmost goal to strike fear in the hearts of his opponents -- and, as writer Grant Morrison posits, trains relentlessly to prepare himself for any eventuality he might ever face. For that kind of life to be believable in the comic book medium, must we also believe that Batman is inevitably insane?

In his much-acclaimed storyline

Batman RIP, Grant Morrison sets as Batman's mind the battlefield for a war between Batman and his enemy the Black Glove. From the beginning of Morrison's run, the Glove has worked to drive Batman insane; in

RIP, the Glove succeeds, but with the unforeseen consequence of pushing Batman to a hidden second persona. In this alternate guise, Batman recalls some of his strangest cases -- including Bat-Mite and the Batman of an alien world -- leading both Batman and the reader to wonder how Batman could have kept his sanity all this time.

It is at the point when Batman's newest paramour Jezebel Jet says she understands Bruce Wayne's pain that Batman suspects she's part of the Black Glove's trap; the implication is that Batman knows no one can ever truly understand him. Toward the middle of the book, Jezebel questions whether Bruce Wayne might be the Black Glove, challenging himself to a battle of wits, and indeed in this scene Batman does seem paranoid and self-destructive. Morrison succeeds in causing the reader to doubt Batman and making Batman seem insane, and now must either confirm this insinuation or refute it.

That Morrison reveals Batman has a long-time "scar on his consciousness" -- a post-hypnotic suggestion that may explain away his "grim and gritty" era -- only furthers the argument for insanity.

The arguments Morrison offers for Batman's sanity are varied and -- likely on purpose -- inconclusive. First, Morrison puts a great deal of pressure on Robin both in

RIP and the "Last Rites" storyline included in the

Batman RIP collection, as the force that's kept Batman sane all these years. Here, Robin is the yin to Batman's yang, the bright spot that keeps Batman's darkness from growing too great. There's also the sense that Robin speaks truths that Batman, captive to his own superheroic delusions, might not want to face, as when the young Robin Dick Grayson asks whether an apparent romance between Batman and Batwoman Kathy Kane might end the Dynamic Duo's partnership.

This is the same theory Jeph Loeb puts forth in

Batman: Dark Victory, and it's sensible even as under heavy scrutiny it reflects poorly on Bruce Wayne himself.

Second, Morrison suggests -- as he did perhaps overmuch in his run on JLA -- that Batman always, invariably, one step ahead of his enemies, and therefore even his proposed insanity has a way of being sane. Morrison's characterization of Batman has always been as the uber-human, ever prepared; we learn in

RIP that even Batman's craziest delusions, the impish Bat-Mite, have in their aspect a basis of reason. In one sequence, the Joker notes that whenever he escapes his prison box, Batman always manages to build another box around the first; in the fact that in

RIP Batman even has a fail-safe personality for his enemies driving him insane, Morrison posits that what might seem like Batman's insanity to the reader is instead a super-sanity that neither we, Batman's allies, nor the Joker might ever truly comprehend.

This has the effect of making every Batman story that Morrison writes like an episode of

Columbo, where the detective knows who committed the crime from the outset and it's incumbent upon the reader to catch up. As in Morrison's

JLA: New World Order, Batman is never in as much real danger as the audience just thinks he is. The suspense of

RIP comes in the reader's concern over Batman's state of mind, the hurt he might feel at the death of his loved ones or over a shocking betrayal, only for Morrison to reveal that Batman's been hip to the Glove's plan all along and that these things were never truly at stake.

It's these twists in the story's mystery that distinguishes it. At the outset the reader believes they're teamed with Batman (that is, we share the knowledge Batman has) against an unknown foe; when Morrison reveals that foe, it's a revelation that alters the reader's perception of the entirety of Morrison's

Batman run, which is no small feat.

In the end, however, the reader learns that Batman's actually known the Glove's identity almost from the beginning. Whereas the reader thought we shared Batman's perspective solving the Glove's mystery, we actually only knew as much as the Glove solving Batman's mystery, and it's this turn that makes

RIP a keeper. These aspects, which play with the reader's head as much as Batman or the Glove's, raise

RIP above a story that, with Batman targeted by a mystery villain and condemned to Arkham Asylum, might otherwise feel "done before" to longtime

Batman readers.

What also distinguishes

Batman RIP is Grant Morrison's use of a number of Silver Age Batman stories (to be collected in a

Batman: The Black Casebook trade paperback). "Robin Dies at Dawn" from

Batman #156, "Batman -- The Superman of Planet X" from

Batman #113, "The First Batman" from

Detective Comics #235 and others are all out of continuity (or at least un-referenced) as of

Crisis on Infinite Earths; Morrison's story brings them back, if even only as hallucinations in Batman's mind. I've greatly appreciated this post-

Infinite Crisis trend in DC Comics to rejuvenate rather than sweep under the rug old stories of their characters (Brad Meltzer did this well in Justice League of America: The Tornado's Path as well), and these details are ultimately what make

RIP a classic.

I don't believe Grant Morrison means for us to believe Batman is crazy, though ultimately I believe his arguments for insanity are stronger than his arguments against. The subconscious trigger with which Batman struggles in

Batman RIP is "Zur En Arrh" or possibly, Morrison alludes in the end, "Zorro in Arkham." To be a hero in Gotham, Morrison suggests, perhaps you can't help but be a little nuts.

[Contains full covers, pages from DC Universe #0, sketchbook section.]Next week kicks of Collected Editions' guest review month, featuring reviews of trade paperbacks and graphic novels from a variety of major and independent comics publishers, written by a great group of guest bloggers. Don't miss it!

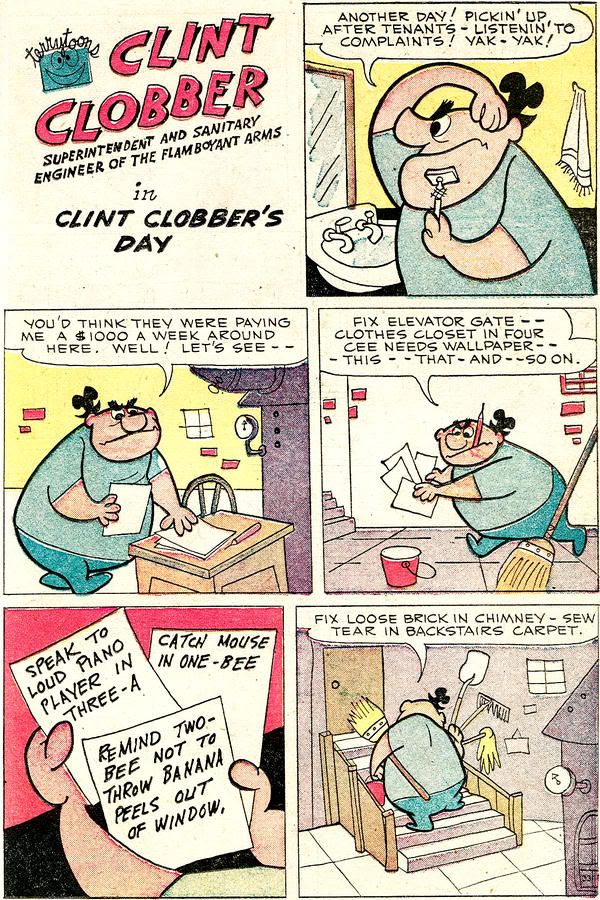

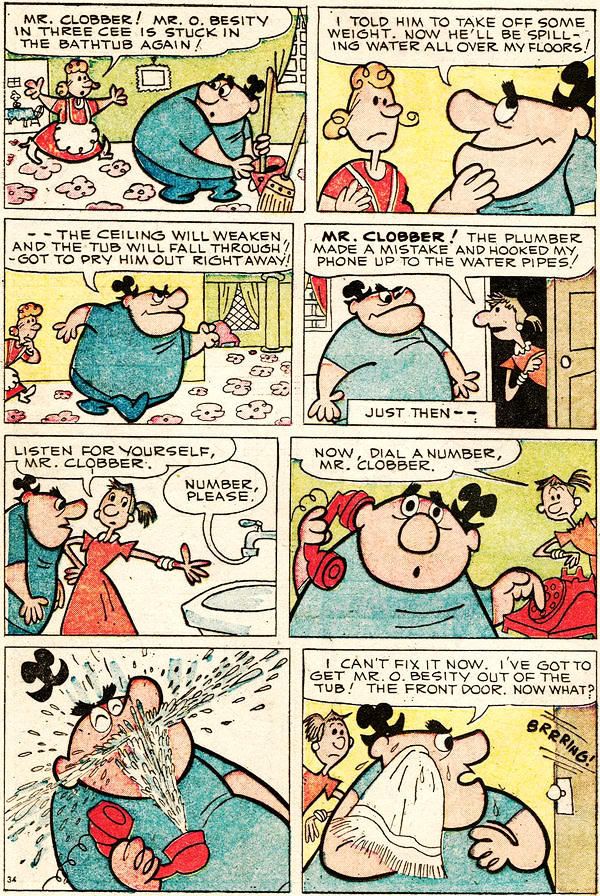

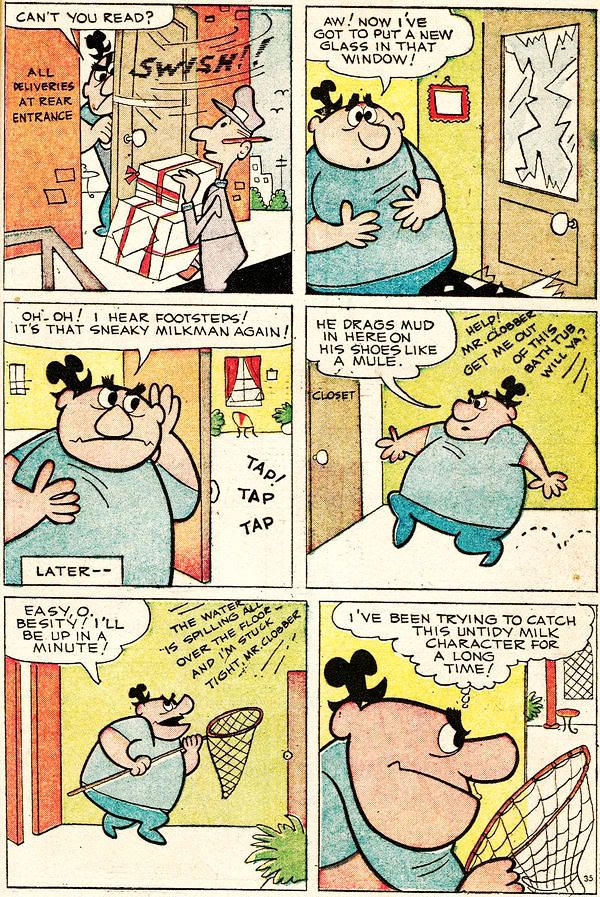

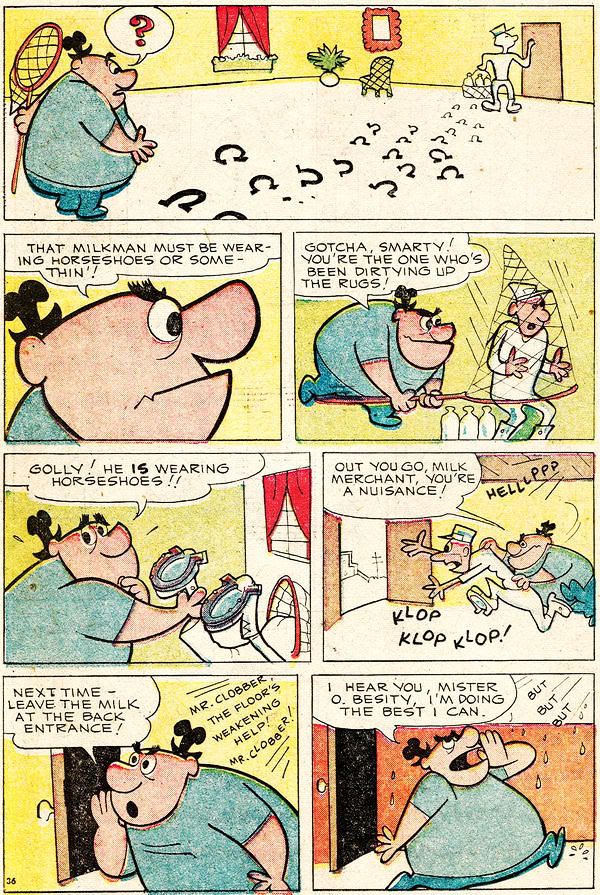

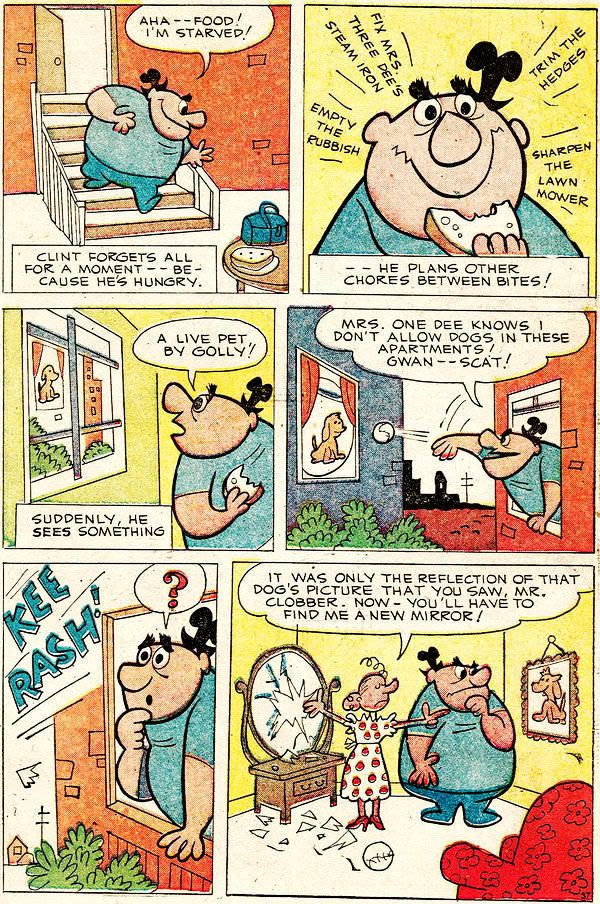

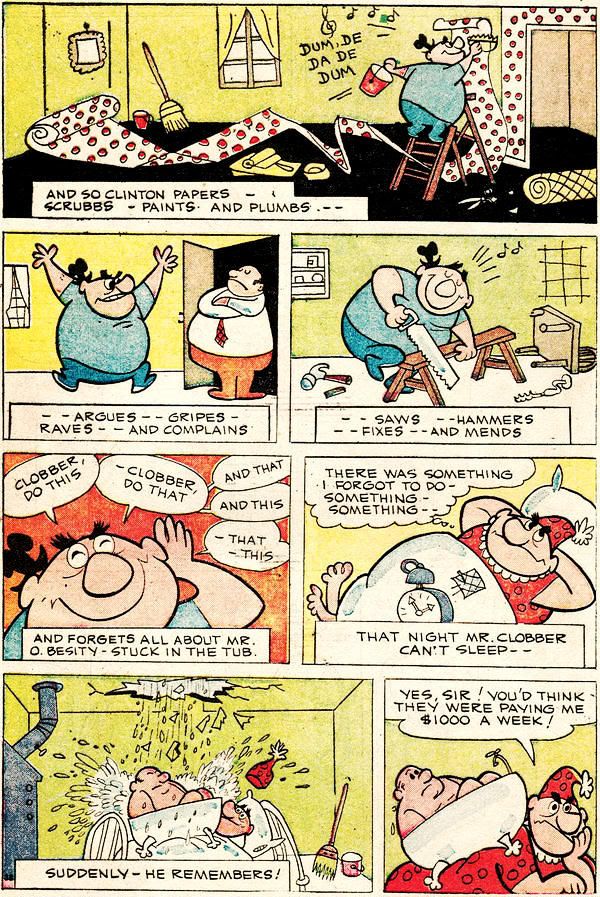

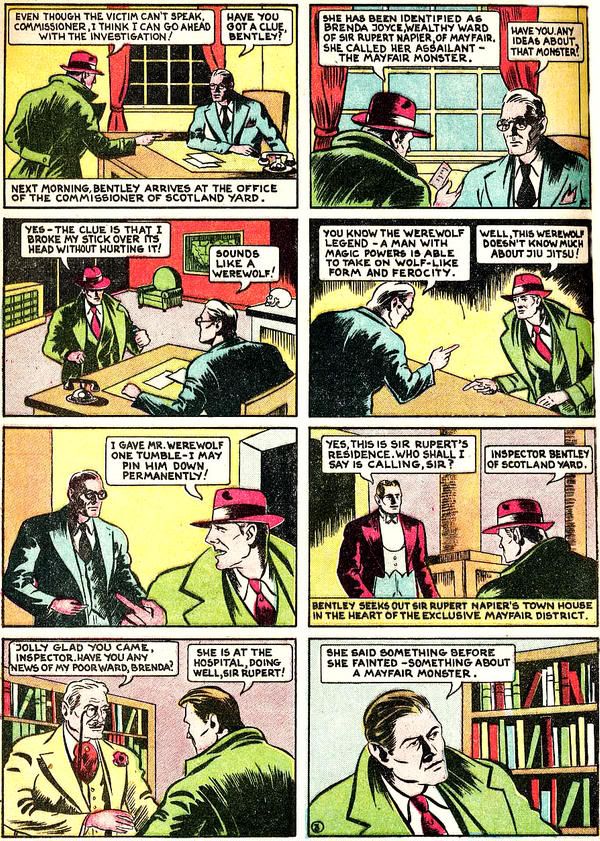

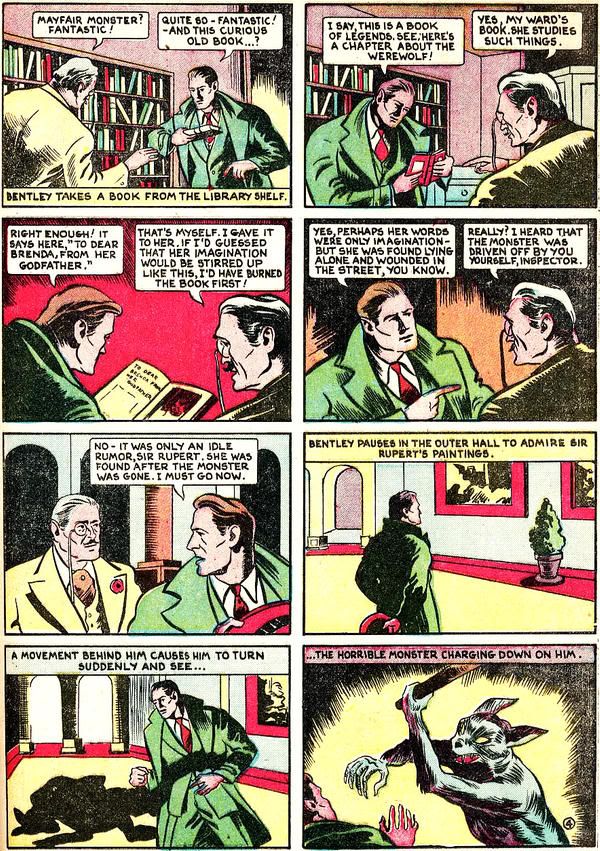

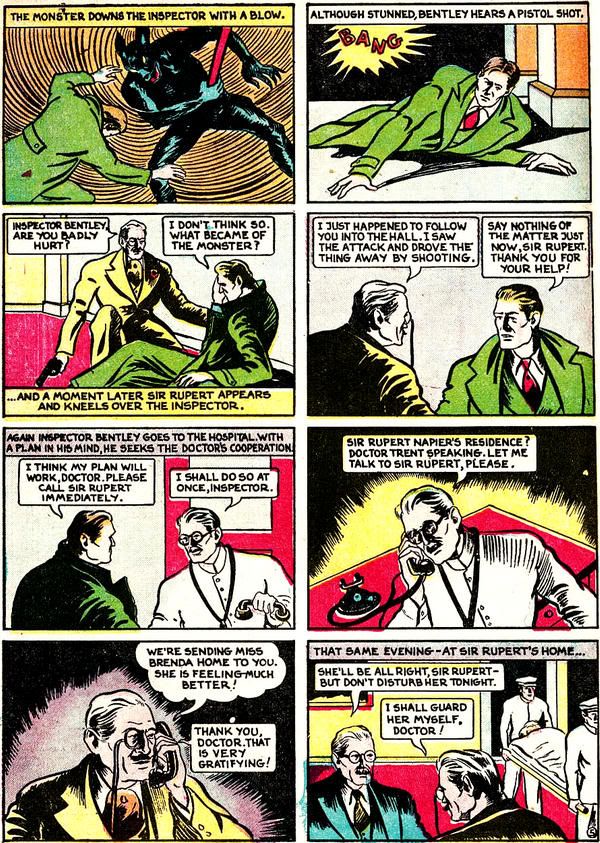

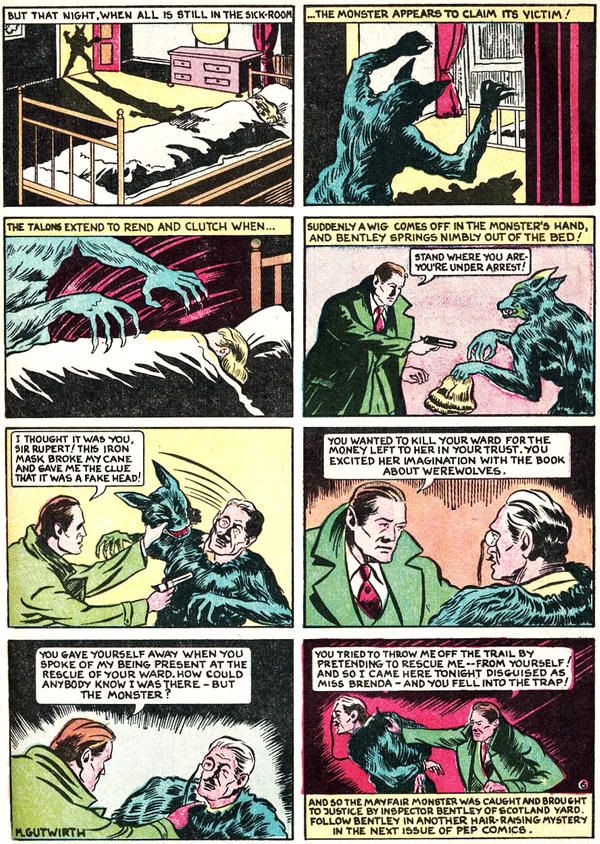

This comes from Boy Comics #13, December 1943. It's drawn by Norman Maurer, a staple of Charles Biro's comic book bullpen for several years. Maurer partnered up with Joe Kubert in the early 1950s. At St. John Publishing they unleashed 3-D comic books on the world.

This comes from Boy Comics #13, December 1943. It's drawn by Norman Maurer, a staple of Charles Biro's comic book bullpen for several years. Maurer partnered up with Joe Kubert in the early 1950s. At St. John Publishing they unleashed 3-D comic books on the world.